BLAST #2

Welcome to BLAST Issue 2

July 2022

A BUSY SUMMER FOR THE MODERN BRITISH ART MARKET BOTH IN THE SALEROOMS AND THE ART FAIRS.

Bonhams

London’s summer auctions of Modern British Art began at Bonhams in late June with a sale that racked up £3.5 million against a £1.6 million pre-sale estimate (prices in this report include the buyers’ premium, estimates do not). The sale got off to a supercharged start with a group of naïve ship paintings by the Cornish fisherman, Alfred Wallis, who was a major influence on the likes of Ben Nicholson and Christopher Wood in the 1920s and 1930s. Wallis is so often faked that provenance has become a key ingredient in establishing authenticity, and these works had been owned previously by the collector, Jim Ede, Bernard Leach, the potter, or the artists Ben Nicholson and Sven Berlin, all of whom knew Wallis personally.

Alfred Wallis (1855-1942), Three Trees. Courtesy Bonham’s.Christopher Wood (1901-1930), Drying Sails, Mousehole, Cornwall. Courtesy Bonham’s.The resulting confidence helped Bonhams to sell all seven examples mostly at double and treble estimate prices up to £120,000 for the one Ben Nicholson owned. The sale was also notable for a record £479,100 given for a 1930 view of Mousehole in Cornwall by Christopher Wood. Although unsigned, it is recorded in Eric Newton’s 1938 catalogue for Redfern and previously belonged to Leonard and Dorothy Elmhirst who owned Dartington Hall.

Another significant result was a triple estimate £516,900 given for ‘Stringed Figure’ 1966, a record for a painting by Barbara Hepworth (as opposed to a sculpture, of which more later).

Dame Barbara Hepworth (1903-1975), Stringed Figure. Courtesy Bonham’s.Sotheby’s Jubilee Auction

At London’s £425 million pounds auctions of Modern and Contemporary Art a week later, British art was given double billing by Sotheby’s. Their sale of ‘the best of British art’ to celebrate the Platinum Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II was not a complete triumph, however, as it realised £72.3 million, just below the estimate. Although this market has been strong, especially for the best examples, it resists over egged reserve prices.

Contemporary women artists were first out of the blocks and where estimates were low and enticing, results were rosy. For example, a burnished terracotta pot by ceramic artist, Magdalene Odundo, had a tame estimate (£50/80,000), considering her market form, and sold to a US phone bidder for £302,400.

Pauline Boty, With Love to Jean-Paul Belmondo. Courtesy Sotheby’s.And the now conservative looking £200,000/£300,000 estimate on 22-year-old artist (see BLAST #1) Lisa Yukhnovich’s Rococo inspired ‘Boucher’s Flesh’, 2017, attracted multiple bidders including one from Hong Kong before selling to a phone bidder for £2.3 million- the second highest price for the artist.

The first record of the sale came when a 1962 portrait of the French film star, Jean-Paul Belmondo, by the British pop artist, Pauline Boty, who died tragically young in 1966, soared to a record £1.2 million over a £500,000/£800,000 estimate – the highest yet for the artist. The painting had been consigned by a recently divorced French lady who bought it when the artist was first rediscovered in 1999 for around £4,000. Pushing the price up as underbidder was Phillip’s Chairman UK and Europe, Hugues Joffre, who was the organiser of the big British Pop Art show at Christie’s in 2013 when he was their worldwide head of Twentieth Century Art and who still retains an interest and clients in this field.

Frank Auerbach, Head of Gerda Boehm. Courtesy Sotheby’s.The other record of note was for Frank Auerbach’s thickly encrusted Head of Gerda Boehm, 1965. The painting had previously set a record £3.8 million when Sotheby’s sold it from the David Bowie collection in 2016. The buyer then, and seller now, was Lebanese collector, Fahd Hariri, who had accepted a guarantee on the painting and an estimate of £2/£3 million. But the guarantee was not needed as the painting was bid up by UK art advisor Gilly Kinloch before selling to a phone bidder for £4.1 million.

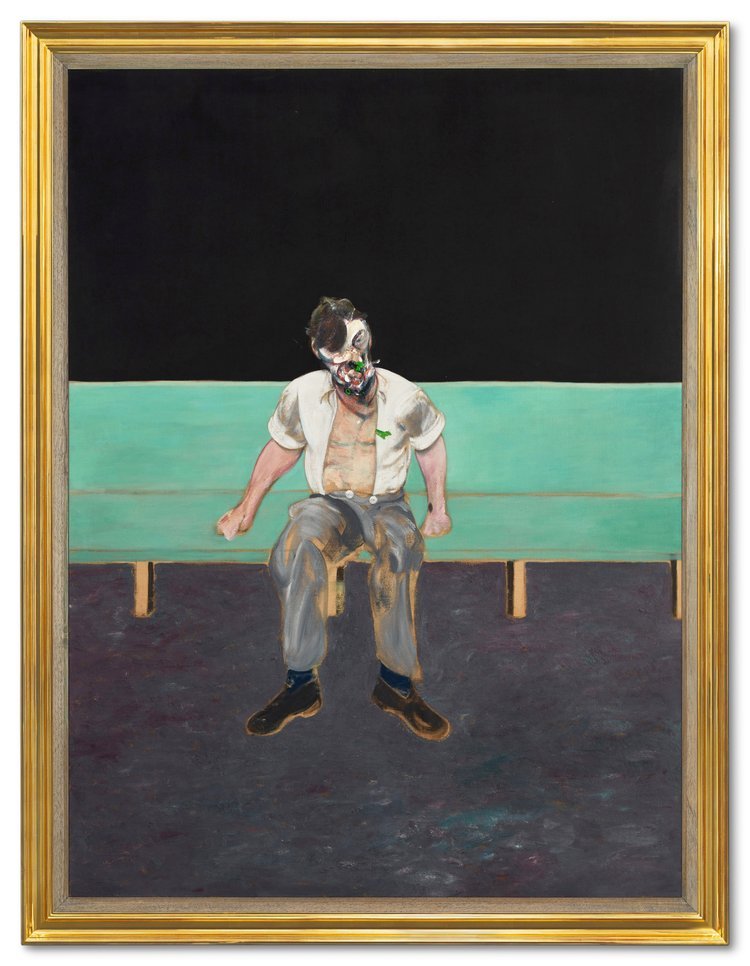

Top lot of the sale didn’t fare so well, though raises some fascinating provenance questions. Francis Bacon’s Study for Portrait of Lucian Freud, 1964, was originally the centre panel for a triptych that had been split up. Single panels from triptychs never do that well, and this one, although guaranteed with an estimate in the region of £35 million, appeared to sell to the guarantor after only 2 bids, for £43.3 million.

Francis Bacon, Study for Portrait of Lucian Freud, 1964. Courtesy Sotheby's.Maybe the new owner of the centre panel can bring the three together again, for a while at least, for the first time since 1964 so we can judge why Bacon uncharacteristically allowed a triptych to be split up. The reason may of course have been money in that this central panel was sold by Marlborough Fine Art soon after it was painted to the aristocratic collector, Colin Tennant, who had numerous Freuds but appeared not to want the Bacon side panels. Sometime later, Tennant sold the painting through the Gallery Galatea in Milan, which sold Bacon’s work to the likes of Gianni Agnelli and Sophia Loren. But, tantalisingly, the trail of ownership then goes cold right up to and including the Sotheby’s sale. Marlborough hung on to the side panels until after Bacon died in 1992. One of them was gifted by them to the Israel Museum in Jerusalem and the other was sold at auction in 1993 when it was bought by British collector, Joseph Lewis.

After this, the second half of the sale seemed to slide. A large six panel Yorkshire landscape by David Hockney with a £10/£15million estimate, received a single bid from London dealer Offer Waterman, at £9.5 million, which was below the reserve, and did not sell. A Banksy of Winston Churchill with a Mohican haircut, Turf War, with an excessive £4/6 million estimate, received no bids and was withdrawn at £2.3 million. Works by Edward Burra, Hurvin Anderson and Damien Hirst were not quite up to their estimates and did not sell, and others by Bridget Riley, Sean Scully and Gilbert & George sold below their low estimates. One of the Riley’s, Tinct, bought in 1992 for £15,500, did realise a good return, however, selling for £2.3 million. But Gilbert & George’s Swear, 1985, bought in 2011 for £330,000 sold for only £126,000, so made a loss.

Sotheby’s Modern British

Sotheby’s then staged a Modern British day sale for lower valued work which came in at a solid £6.9 million, around the mid presale estimate. Christopher Wood was again one of the top sellers, with a £151,000 Breton coastal view

Cedric Morris

Sir Cedric Morris, Still Life with Tiger Moth. Courtesy Sotheby’s.Among the strongest sellers was a handful of paintings by the East Anglian flower painter, Cedric Morris, which had been passed down by descent to the children of the former diplomat and chairman of the National Art Collections Fund, Sir Peter Wakefield, who died in 2010. All sold far above estimate and for multiples of their cost. To take two examples: in 1996, Wakefield bought a floral still life, The Schmake Pot, 1960, for £8,625. In June this year it sold for £239,400. In 2002 he bought a painting of a vase of Spring Flowers at Christie’s for £6,000. At Sotheby’s in June, retitled more accurately as Still Life with Tiger Moth, it was estimated at £20/£30,000 and sold for £226,800. It may come as no surprise that the Morris record of £350,000 set in 2020 of a painting of cabbages, also came from Wakefield’s collection.

Competition for Morris’ flower paintings had been bubbling up for some years when in 2016,one sold for a record £87,000 to Richard Green, and then the next year another sold to rival dealer, MacConnal-Mason, for £160,000. Philip Mould then joined the throng, focusing on Morris’s relatively cheaper (and undervalued?) landscapes. The Art Sales Index calculated that between 2014 -2017, average prices for Morris increased by a mind-boggling 1,500 percent. The rate may have gone down, but the upward gradient continues.

Christie’s

Christie’s did not stage a Modern British Art sale as such, but included a number of examples in its Modern and Contemporary sales. Dealing with the young ones first, the action continued from my last BLAST report for 31-year-old Rachel Jones whose Spliced Structure 2019 was not the largest work of hers to come to auction but it carried the highest estimate at £100,000/£180,000. And maybe the heat is wearing off as, even though it sold over-estimate at £403,200, that was far short of a similar painting called Spliced Structure that made £910,000 ($1.2 million) in March.

40-year-old Scottish figurative painter, Caroline Walker, had nine works under the hammer or online that week, with a domestic interior, Preening, 2018 carrying the highest estimate of £100,000/150,000 at Christie’s, by far the highest estimate yet for an artist whose work first made waves at auction in 2019 when a work from the Saatchi Collection made a five time estimate £31,250. Since then, her prices at auction have leapt to £80,000 and then to a x 5 estimate £327,600 at Phillips in March. But Preening, with its emboldened estimate, attracted sparse competition and sold on the low estimate for £126,000, suggesting that collectors are resisting the rising estimate syndrome.

A painting by regular favourite Jadé Fadojutimi (see BLAST#1) who also, since 2020, normally sells at multi-estimate levels, only sold at a mid-estimate £567,000. Hadn’t anyone heard that she was about to be signed up by Gagosian? Or perhaps the market really is cooling.

And then came the big surprise of the sales, the failure of Cecily Brown’s sexually charged ‘Single Room Furnished’, 2000, to sell with a £1million low estimate. Mind you it had only cost £176,000 back in 2006, but perhaps it was another sign that buyers in this very frothy sector of the market are beginning to dig their heels in. Since November 2019 over fifty paintings by Brown have been sold at auction for prices up to $6 million, and only 2 of note unsold. Enquiries at Christie’s were met with the familiar response: “There was good pre-sale interest which didn’t convert to bids in the saleroom on the day,” which just means bidders were being cautious. Brown’s dealer, Thomas Dane, will be hoping this won’t unduly affect the exhibition he has scheduled for her in October to coincide with Frieze.

Lot 33 |BARBARA HEPWORTH (1903-1975) Hollow Form with White Interior. Nigerian guarea wood with white paint

Height (excluding base): 38 1⁄2 in. (98 cm.) Width (excluding base): 31 3⁄4 in. (81 cm.) Depth (excluding base): 17 in. (43.2 cm.) Height (including original black lacquered wood base): 40 1⁄4 in. (102 cm.)

Carved and painted in 1963; this work is unique. Price Realised: GBP 5,785,500. © Christie’s Images Limited 2022The standout female artist at Christie’s instead was Barbara Hepworth whose large carved wood Hollow Form with White Interior, 1963, sold within estimate for a record £5,785,500 ($7,098,809). Advisors Beaumont Nathan were the underbidders for a client. “It is a masterpiece by the greatest female sculptor of the 20th century”, said Hugo Nathan. “ She is under-priced compared to other 20th century masters like Moore or Giacometti. In five years that piece will be worth a lot more. I am glad we tried; but sad we failed,” he said. Together with three other Hepworth sculptures that sold that week, her total for the series came to over £10 million.

Phillips

At Phillips, recent Slade School of Fine Art graduate and Timothy Taylor gallery signee, 31-year-old Antonia Showering’s figurative painting We Stray sold for a quadruple estimate £239,400 – just a shade above her previous £226,00 record set in her first appearance at auction. Other multiple-estimate, though not record, prices were set for Caroline Walker, and Flora Yukhnovich, probably the pick of this bunch, whose Moi Aussi je Déborde, sold for a x 5 estimate £1.7 million.

Perhaps the most interesting result was for Three Red Boxes and Circle, a 1967 painted stainless steel sculpture by David Annesley, an artist who appeared to have fallen into oblivion following a glittering career start in the 1960s as a follower of Sir Anthony Caro in the Waddington Galleries stable. His previous record, according to Phillips, was just $81, set in 1997.

But this sculpture generated some competition, selling for £113,400. Its story only began to unfurl after I visited the Masterpiece London fair (see below).

David Annesley, Three Boxes and Circle, Painted Steel, 1967. Courtesy Philips.Masterpiece

Masterpiece this year was more packed with dealers promoting Modern British Art than ever. Having been a minor ingredient of the luxury London fair when it began in 2010, this year, Modern British art played a dominant role with some 30 galleries exhibiting work by Modern British artists as a major feature. Peter Osborne of the Osborne Samuel gallery, who is on the fair’s committee, said that, apart from reflecting the strength of that market, this was also due to the fall off in overseas exhibitors because of Covid and Brexit complications and the easy access in the UK to Modern British dealers who could fill those gaps.

Michael Craig-Martin RA, With Red Shoes, Courtesy Richard Green.Tactically placed within yards of the entrance was the market leader, Richard Green, with a fabulous large Michael Craig-Martin painting of red stilettos which he had bought in the sale of Clodagh Waddington’s collection for a record £325,000 and was now offering for £650,000 – more like the prices charged by his gallery, Gagosian, – and a luscious painting of a pile of books by William Nicholson that he bought from the Siegfried Sassoon collection for £550,000. Sales were flowing at a slightly lower price level said Jonathan Green, who numbered sales of paintings by Matthew Smith, William Scott and Adrian Heath at up to £550,000 each amongst his achievements. Nearby, a wall full of Lowry’s at MacConnal Mason saw half of them sell, though the most expensive at £4 million hadn’t found a buyer just before the close.

Walking Woman, 1984, presented by Osborne Samuel at Masterpiece London, Ben Fisher Photography. Courtesy Masterpiece LondonSuitably for a fair that majors in three-dimensional works of art from millennia old gogottes and antiquities to jewellery and furniture, modern sculpture sales flourished on several stands. Osborne Samuel led the way with a seven-foot Walking Woman, 1989, from an edition of nine by Lynn Chadwick that had been on long term loan to Salisbury Cathedral which sold close to £2 million, a price that has only been bettered twice at auction, but never from this edition.

Emma Ward at Simon Dickinson filled their central floor space with Modern British sculptures by Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Emily Young (£80,000) and Jacob Epstein (a portrait of Kathleen £28,000) and sold them all. The best Epstein at Masterpiece, though, was a voluptuous naked bust of Francis Bacon’s pregnant model, Isabel Rawsthorne, on Jonathan Clarke’s stand. But while he had been selling paintings by Ivon Hitchens whose estate he represents, no one had bought Mrs Rawsthorne when I visited. There is still an issue knowing how many and which of Epstein’s bronzes were cast by his widow, Lady Epstein, after his death. There is nothing wrong with later or posthumous castings if they were authorised by the artist – as in the cases of Rodin, and indeed Chadwick or Barry Flanagan. “The prices aren’t wildly different,” says Osborne – not like later prints of vintage photographs.

Perhaps the most interesting case of remade sculptures involves David Annesley. After the record sale of one his 60s sculptures at Phillips I saw another untitled example of his work placed on the lawn outside Masterpiece priced by Waddington Custot at £90,000. When the gallery renewed its relationship with Annesley in 2015, they realised that, while most of their sculptures by him had been destroyed in the 2004 MOMART fire, they had been conceived in editions of three and there were still two to be made of each, which is what they are doing now in preparation for a solo exhibition a year or two from now. The work at Phillips was not one of these, having escaped the fire, but was consigned by the gallery to auction. They chose Phillips before Sotheby’s and Christie’s because there is more emphasis on the contemporary in their sales, says director Jacob Twyford, and because the wider, cleaner more open spaces suited the display of the artist’s work better. For Annesley, life as an artist has begun again aged 85.

One encouraging note for the fair was the youthful attendance. Adrian Mibus of Whitford Fine Art sold several paintings by Mildred Bendall and a pair of shiny football boots by pop art sculptor, Clive Barker. As we gazed at a pair of blue suede shoes by Barker, Mibus mused on the number youthful enquiries: “I’ve lost count of the number of people I’ve had to tell about Elvis Presley,” he said.

Colin Gleadell is the art market columnist for The Daily Telegraph and a regular contributor to Artnet News, Art Monthly, and Artsy. Prior to The Telegraph, he worked for the Paul Mellon Foundation for British Art as a researcher, the Crane Kalman Gallery as a gallery manager, and Bonhams auctioneers as Head of Modern Pictures. He worked for ten years (1986 – 1997) as the features editor of Galleries Magazine, whilst also contributing to leading art market publications such as Art & Auction and Art News where he was the London correspondent of the Artnewsletter. He Introduced Sister Wendy Beckett to the BBC for whom he worked as a consultant on market programmes such as the Relative Values series (1991). He also worked as an art market consultant for Channel 4 News.

Gleadell was on the original advisory committee for the 20th Century British Art Fair in 1988, where he has served ever since as it changed its name to the 20/21 British Art Fair, and now the British Art Fair.