THIS IS TOMORROW

Michael Bird’s latest book – this is tomorrow - follows familiar terrain, taking the reader on an entertaining ride through the history of the British Modernist art movement, from its roots in the 1870s, to the turn of the millennium.

It’s quite a thrill. Bird sets off at some pace with a retelling of the Whistler v Ruskin court case in 1877, when the arch-conservative art critic was sued for libel after accusing the American-born artist of ‘flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face’. The case ended in a costly draw, with both parties ending up significantly out of pocket. But it constituted a lively opening to the ongoing national debate about the validity of modern art.

If Ruskin was so incensed by Whistler’s Nocturne paintings, one wonders what he would have made of Cornelia Parker’s exploding shed. Bird ends his journey, hardly taking his foot off the gas, with an exploration of the genesis of the YBA movement, in a very different Britain. Along the way he introduces us to the artists and influencers who laid down the stepping stones towards those unmade beds, pickled sharks and frozen-blood sculptures. We meet Walter Sickert, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, William Morris, Gwen and Augustus John, Duncan Fry, Venessa Bell, David Bomberg, Barbara Hepworth, Henry Moore, Percy Wyndham Lewis, Ben and Winifred Nicholson… you could probably complete the list yourself.

The author is skilful in bringing his protagonists’ personalities to life, and placing them in their historical context, throwing together several strands within stand-alone chapters. Thus in chapter three William Morris, Charles Rennie Mackintosh and Ebenezer Howard vie for attention; in chapter five Roger Fry’s post-impressionist shows are counterposed with Marinetti’s Futurist adventure and the emergence of the New York Metropolitan Museum as the world’s wealthiest buying gallery. And on it goes.

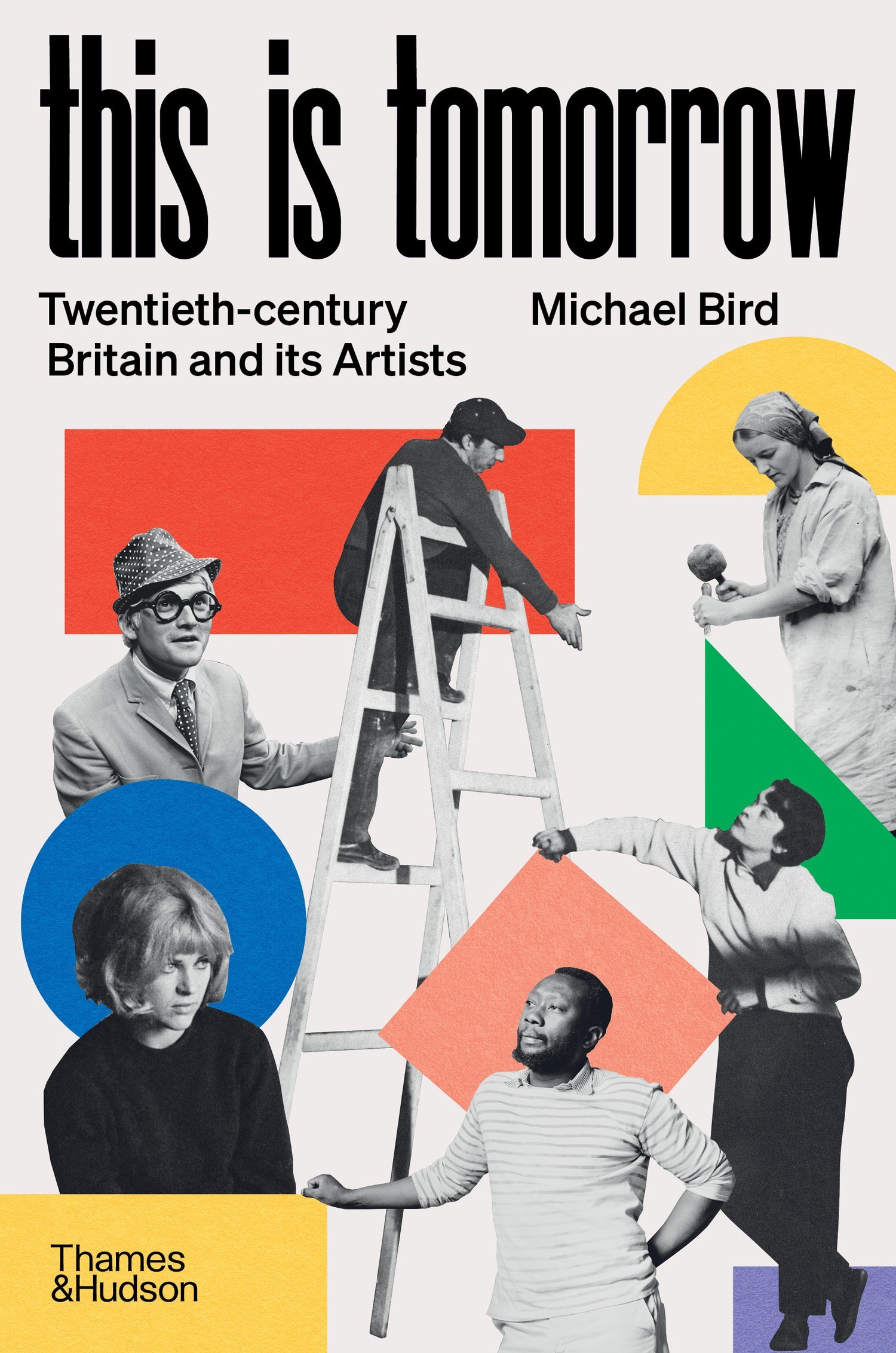

Phew! Happily, Bird is a fine story teller, and his meticulously researched book (which is named after the eponymous Whitechapel Gallery show that paved the way for British Pop Art) wears its erudition lightly. It’s quite the page-turner, then, but also a volume you will most likely keep on an easily accessible shelf for easy future reference. Just don’t judge it by its mid-century-modern cover, which doesn’t do justice to its century-long timespan.